Designing Indian Streets as Social Public Spaces: Contextual design and planning in Bangalore

Master in City Planning Thesis by Sneha Mandhan

Department of Urban Studies and Planning, MIT

Streets in India have traditionally been the public spaces around which social life has revolved. They constitute the urban public realm where people congregate, celebrate and interact. The hypothesis that forms the basis of this thesis is that there is a need to understand and design these urban streets as living corridors through which one perceives and understands the city, and the places where one has daily social encounters.

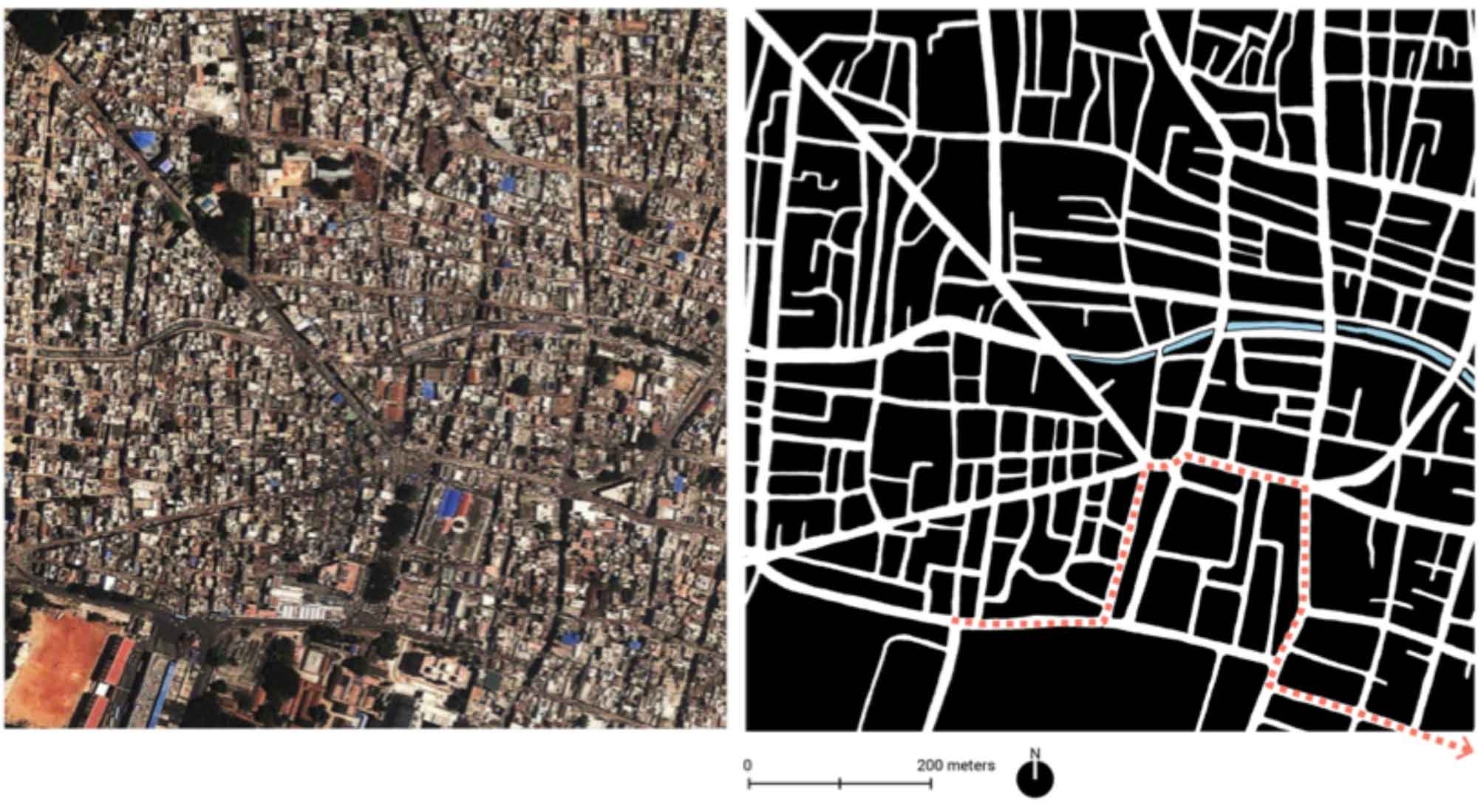

Using Bangalore as a case study, this thesis analyzes spatial and social forces that shape street experience and culture at the scale of the city, the locality, and the street itself. By performing a reconnaissance study and an analysis of the street patterns in fifteen localities within the city, along with a detailed spatial analysis and interpretation of four different types of streets, I shed new light on the social life of different types of streets, and suggest ways in which the stimuli for these social lives can be understood and used to formulate design guidelines for streets in Indian cities that are currently undergoing similar transitions in their development.

Through this process, I propose a method to identify urban typologies that relate to the physical and social conditions that occupy the city, along with a set of criteria that can be used to assess, plan and design streets that are more contextual in nature. A few examples of the neighbourhood and street analyses are included here.

For more information, please see below:

For a full copy of the thesis, please email sneha.mandhan@mail.utoronto.ca

For a photo essay on the crafts of Indian streets, please see here

For a short essay on the research and project conclusions, please see here or here

Meenakshi Koil Street, Shivaji Nagar

Shivaji Nagar was known as Blackpally when it was developed as a part of the Civil and Military Station during the 1800s after the British colonized the city. The workers who came from other parts of the region in search of work settled in the area which is located next to the Cantonment. Shivaji Nagar has one of the two major bus stations in the city and is located on the east end of the central east-west axis of the city very close to Mahatma Gandhi road which is often defined as the center of the city. It is also one of the major street shopping areas in the city and houses both affordable, smaller, local shops and larger chain stores. It also houses several temples, mosques and churches. Russel Market which is one of the oldest markets in the city and is a major local market for fruits, vegetables and flowers is located in this area. The area has smaller plot sizes with buildings upto 4 floors. Most buildings share common walls. The area is dense with certain institutions like the bus station and St.Mary’s Basilica having open space within the larger plots. Vegetation is sparse.

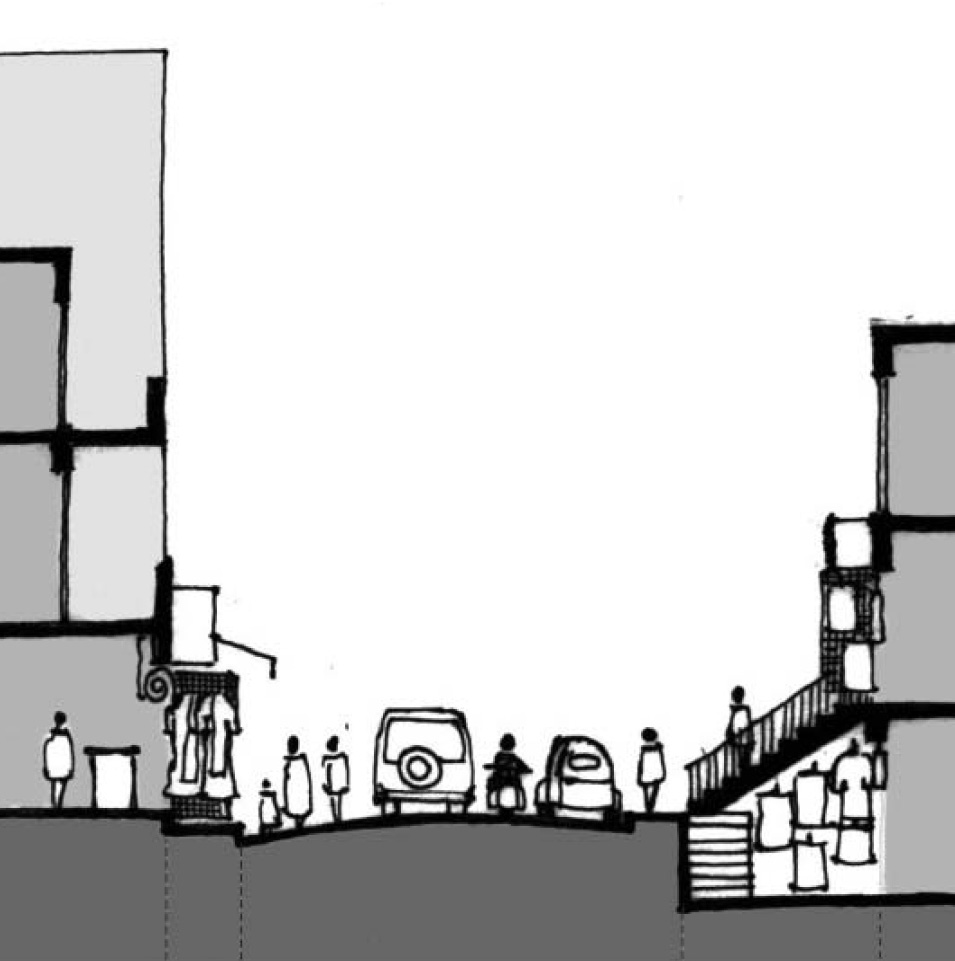

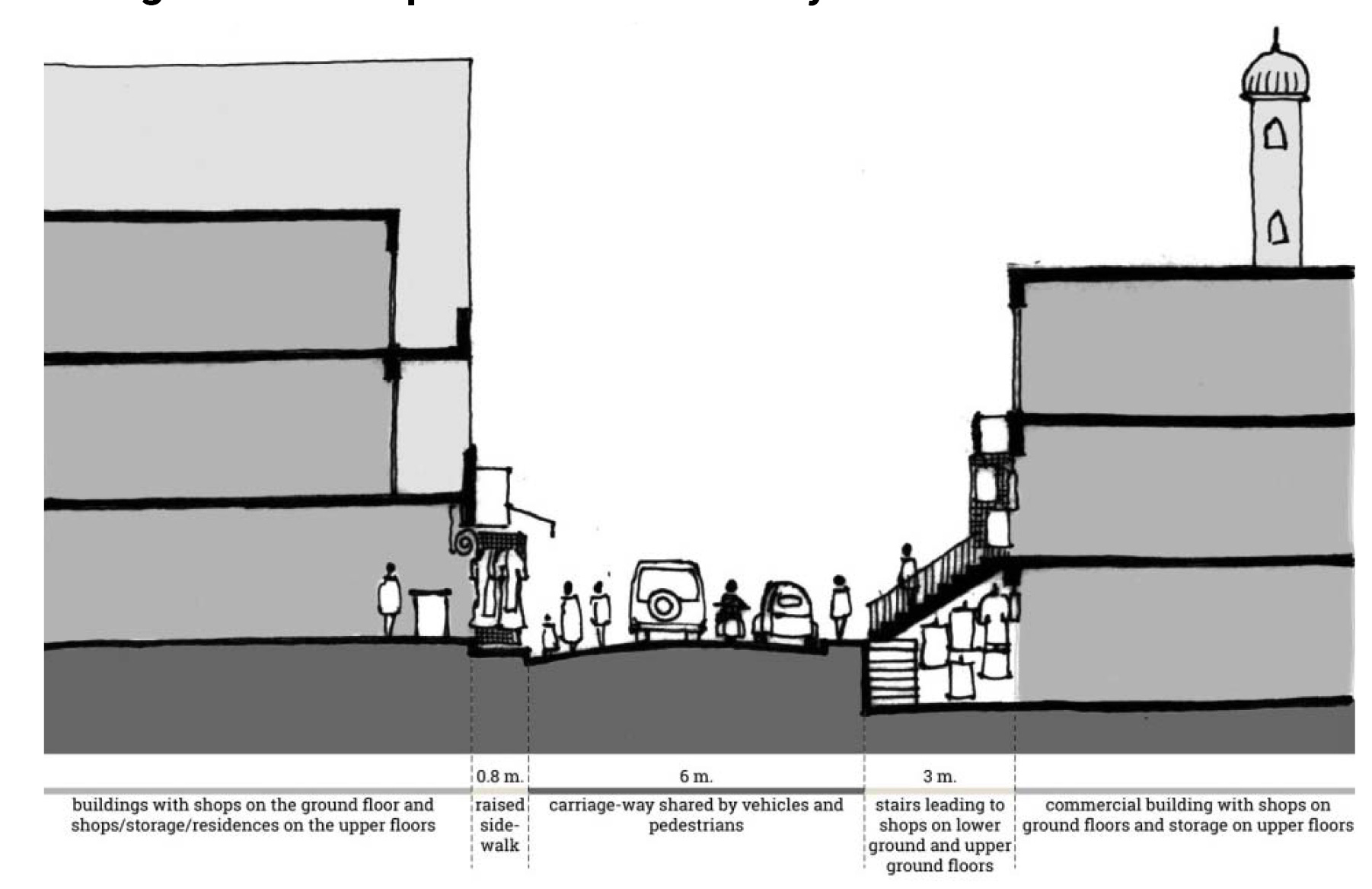

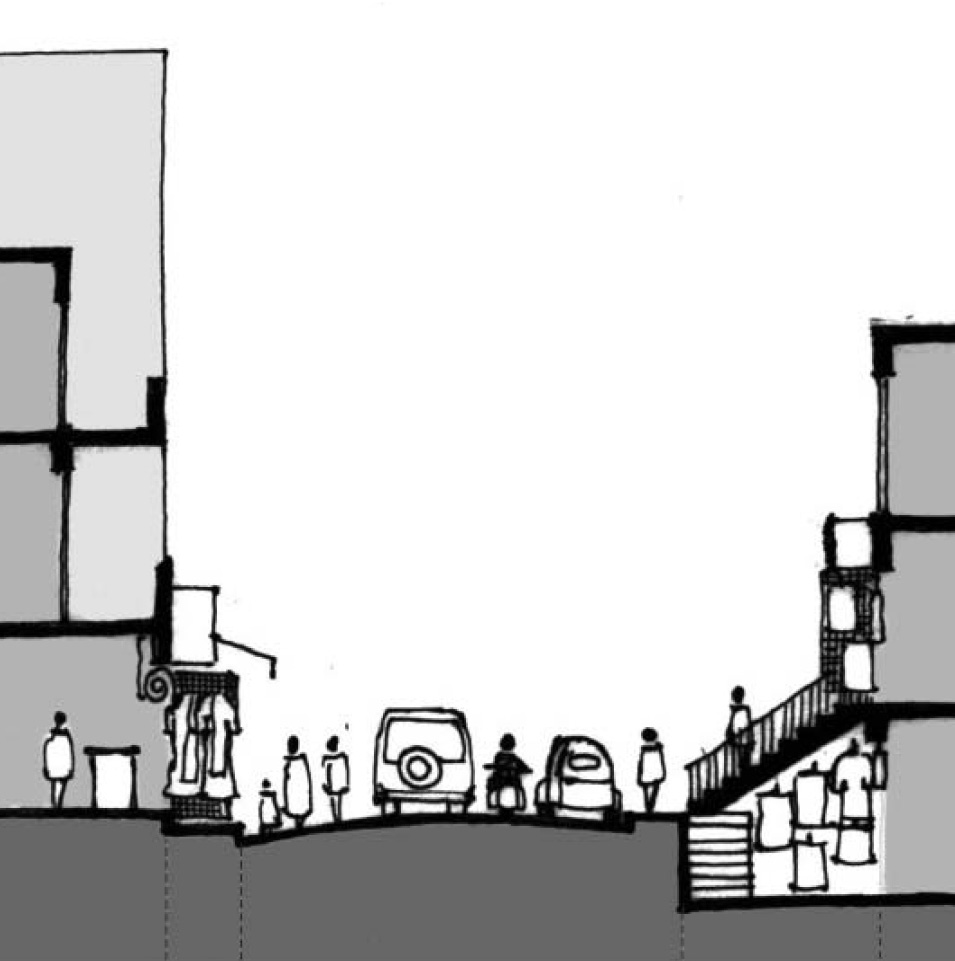

Meenakshi Koil Street runs along a temple between a basilica and a mosque. It is a stage for religious processions not only during festivals but also on a day-to-day basis where people fulfill their daily ritual of prayer on their way to work and home. The street leads from the Shivaji Nagar Bus Station to Russel Market, which is one of the oldest and major local markets for fruits, vegetables and flowers, and to Commercial street which is famous for shops of clothing, and personal and household accessories. This street offers a unique mix of religion, shopping, living and connecting in a way that is flexible and creates a place that changes throughout the day and the year.

This street seemed particularly unique to me because its social life is symbolic of the (often aspirational) secular nature of the city and the country. It allows for different parts of the population to not only respectfully co-exist, but also become a part of a larger culture – one that allows you to not only retain your identity and offer your prayers to whichever God you believe in, but also interact and mingle with humanity as a whole by making them a part of your daily life and becoming a part of theirs.

Gandhi Bazar Road, Basavangudi

Basavangudi was laid out as a part of the ‘hygienic’ residential development for the upper middle class population post the plague epidemic in 1898. It is located south of Chamarajpete and is predominantly residential with the commercial activities focused along the diagonal streets. The older plans of the area show housing allocated in the area by the Bangalore City Improvement Trust based on castes and occupations. The central area in Basavangudi is a large park and smaller parks dot the internal blocks within the grids as well. The area is relatively less dense with larger plot sizes and a predominance of large individual bungalows upto 3 floors high with wide vegetated setbacks along the front, rear and sides. Several large temples like the Dodda Ganapati and the Bull Temple are located in this area. The population is mostly local.

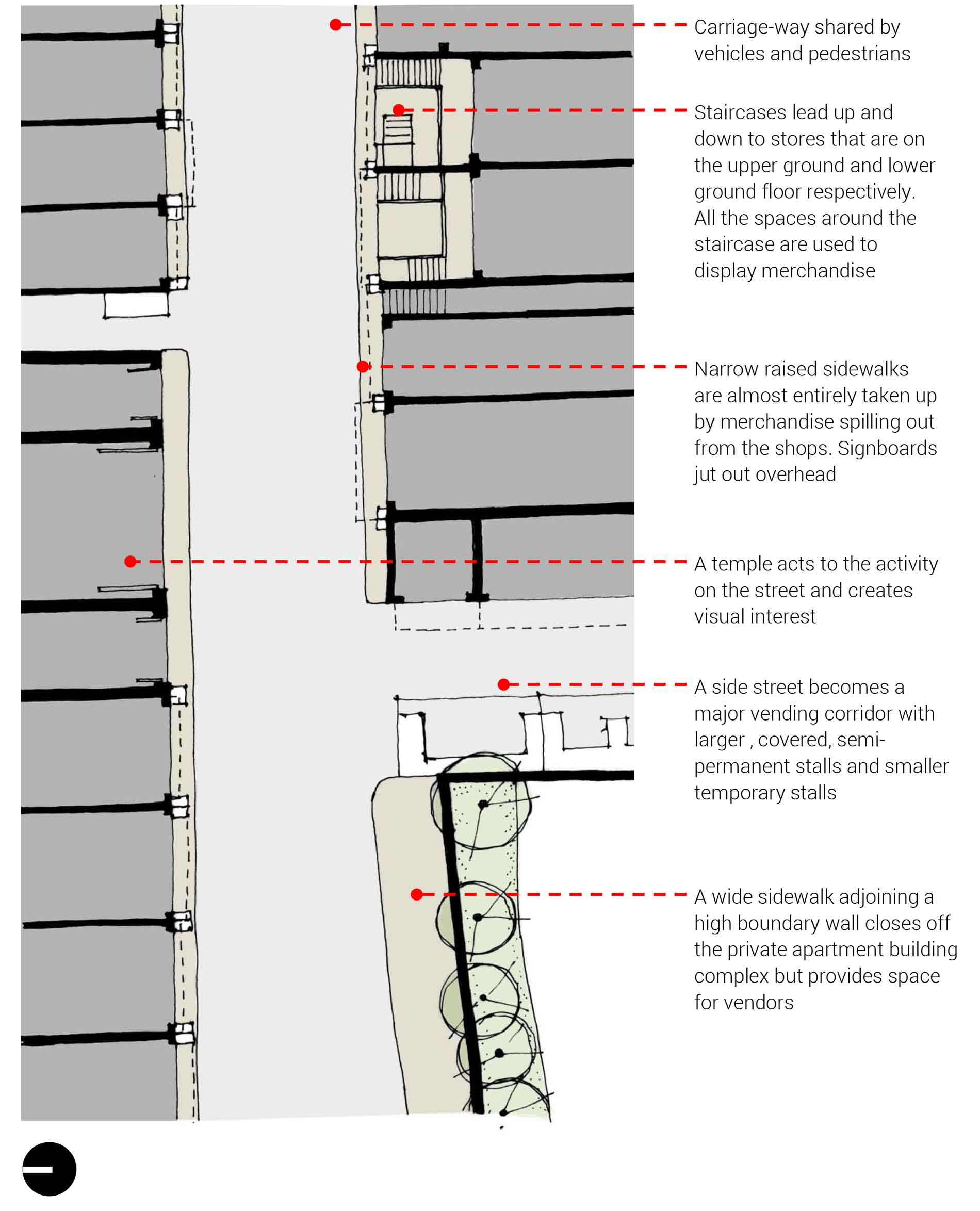

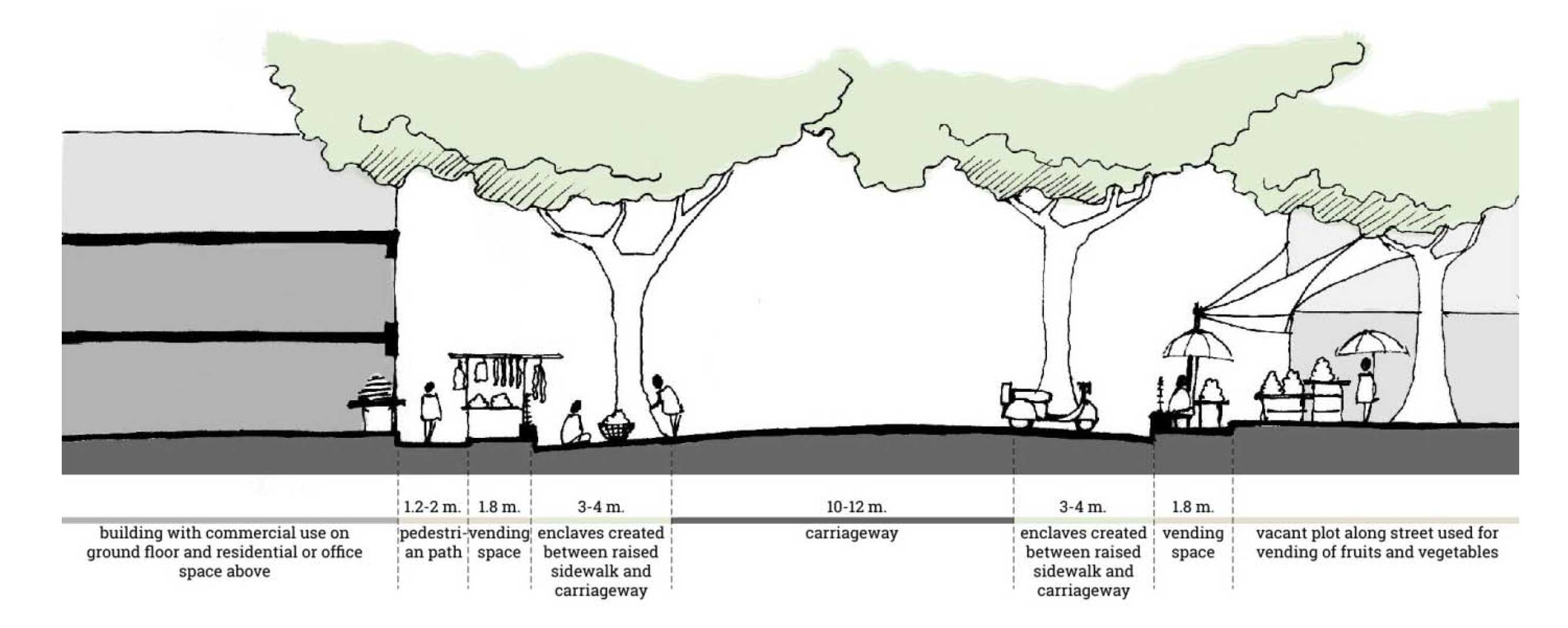

Having a dedicated lane for street vendors that runs along the sidewalk for about half the length of the street, along with shops, small bazaars, and showrooms, this street is unique for its spatial structure and its social essence where people perform their daily ritual of buying flowers, fruits and vegetables from local sellers for their home. Patrons of these shops change throughout the day with the morning and evening consisting of men, women and families partaking in this daily ritual of selecting, haggling, and buying, while during the day women linger buying their daily goods but also stealing glances at sarees and jewellery that spill out of the stores.

This street stands out as the stage on which the mundane chores of daily life are carried out in a way such that the bane choreography of each individual’s movements form a larger rhythm which changes throughout the day in terms of pace and sensory stimulation. Simple activities like haggling with vendors, eating at one of the high tables spilling out onto the street from Darshinis (local restaurants that mostly have only stand-up tables and offer only local delicacies), getting the tyre of one’s car changed, or standing around a paan stall having a smoke, all seemingly mundane chores come together on this one street to form its hustle bustle.

What makes a ‘great’ Indian street?

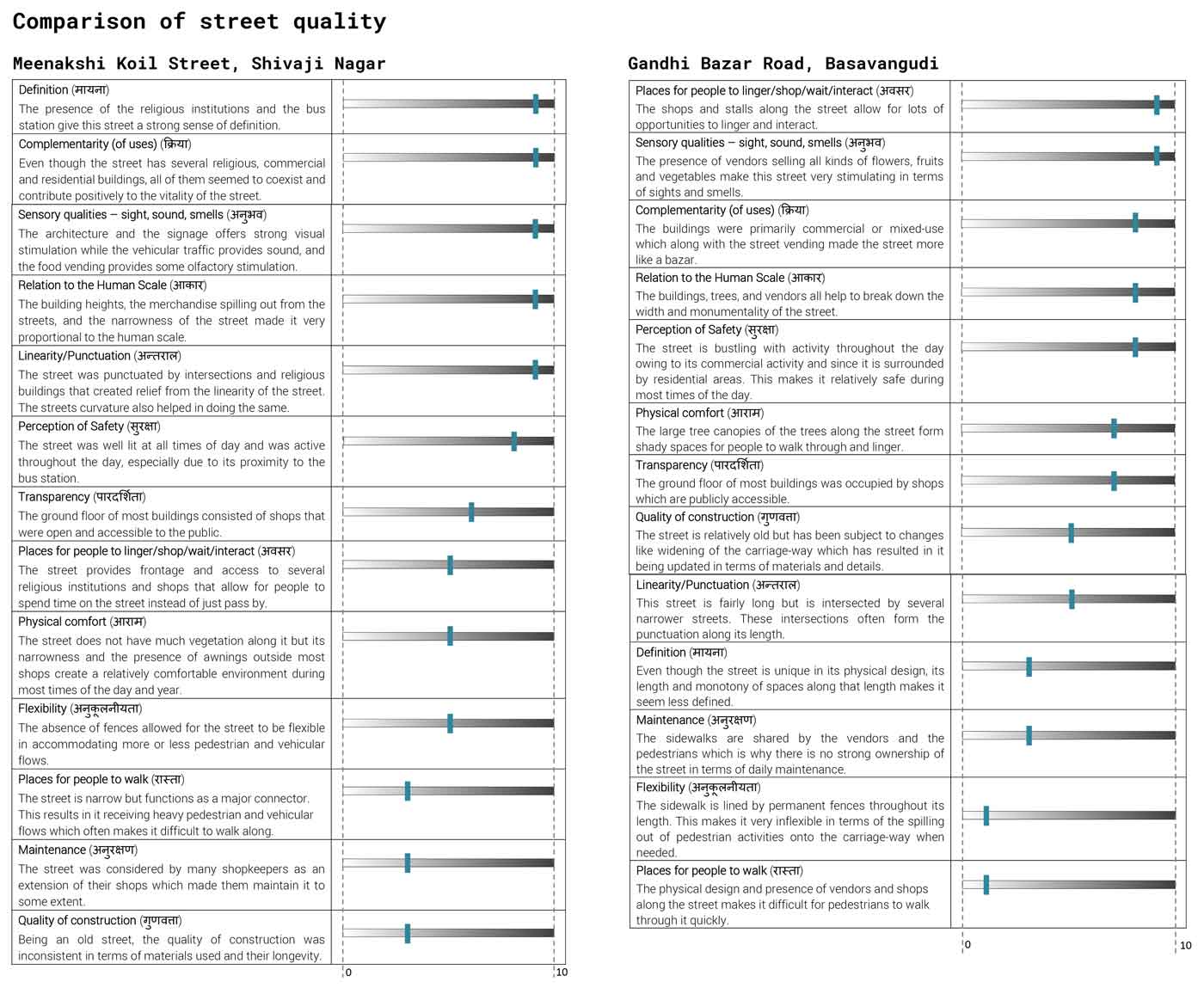

In order to facilitate context-specific design for streets while still providing some level of standardization and optimization for the planning process that is the underlying reason behind the formulation of design guidelines, it is essential to be able to have a specific list of qualities that contribute to and criteria that assess the greatness of a street. These criteria can be used as a comprehensive tool for planning within the local context of Bangalore. In order to be able to analyze and understand streets, there are certain physical qualities of the street that need to be observed. These are the physical qualities that together create the spatial and sensory experience for a user of the street. Allan B. Jacobs identifies thirteen such qualities through his case studies of several American and European city streets (Jacobs, 1995). During my field research, using his list as a starting point, I created an initial list of such qualities for Indian streets. This list was initially developed before the field research was carried out and the qualities and criteria used during the field research for the purpose of analysis and observation. This process helped to add to and subtract from the list which is finally presented below in a comprehensive format.

The tables below show a basic qualitative placement of each street on a spectrum of low to high (0 to 10) for each of the criteria developed for assessment, with the criteria ordered from high to low by their importance for the social and cultural life of that street. The criteria were also given Hindi transliterations which do not directly translate into the same words in English but hint at the same definition in terms of street character. In many ways the Hindi transliterations are richer because they allow for a more local and wider interpretation of characteristics as compared to the English criteria. A brief explanation of the contributing factors was also included for each criteria. This method of assessment can be used as a metric for qualitative assessment of streets throughout the city and for design proposals for future streets throughout the city.