Single-family homes are the anti-collective, so it seems.

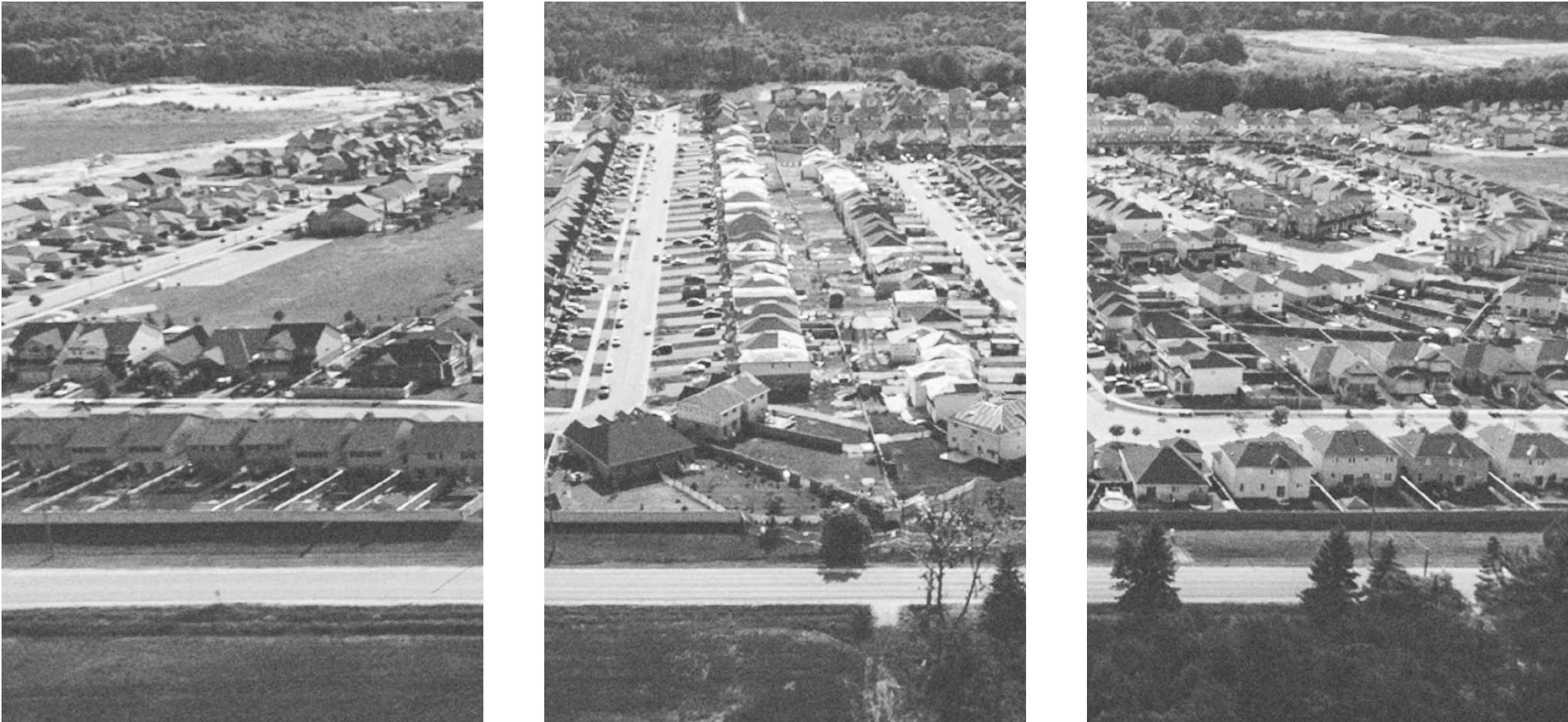

Set on their own piece of private property, and buffered from their neighbors, the single-family home suggests individuality, personal freedom and self-determination. However, during the post-war years in Canada and the United States, single-family homes added up to something more. Developed en-masse as part of very large neighborhood subdivisions, these individual buildings and their occupants were imagined to make up insular communities.

Originally these subdivisions were developed as private enclaves.

Critics of them note that they are designed to foster community within and exclude those who are not part of that community. One motivation for this exclusion was safety — too keep fast moving thru-traffic out of the subdivision so kids could play on the streets and walk to school — but it’s not hard to imagine that the desire to exclude the other was a motivating force in its own right. The subdivision, or neighborhood unit, is at once a mini-collective for its residents and the anti-collective at the scale of the urban region.

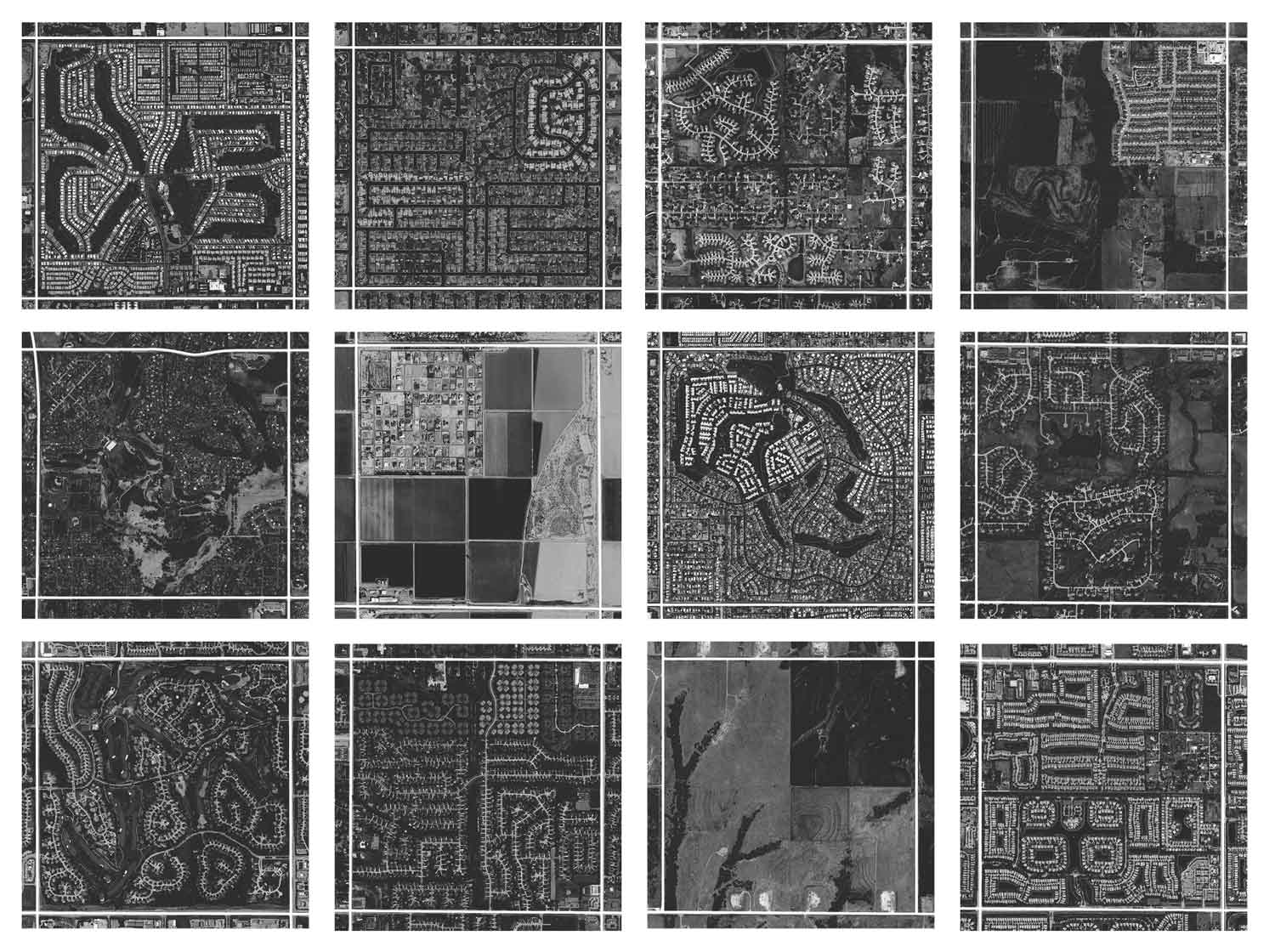

The enclave is the spatial unit of suburban sprawl.

Each enclave is an island, with its own internal logic and a buffer that allows them to be next to almost anything else without having to establish a relationship to it. Within an enclave one may realize almost any image: Italian villas on the countryside, English manors, Venetian Canals or, as is more recently the case, the compact neighborly forms of early mercantilist town centres.

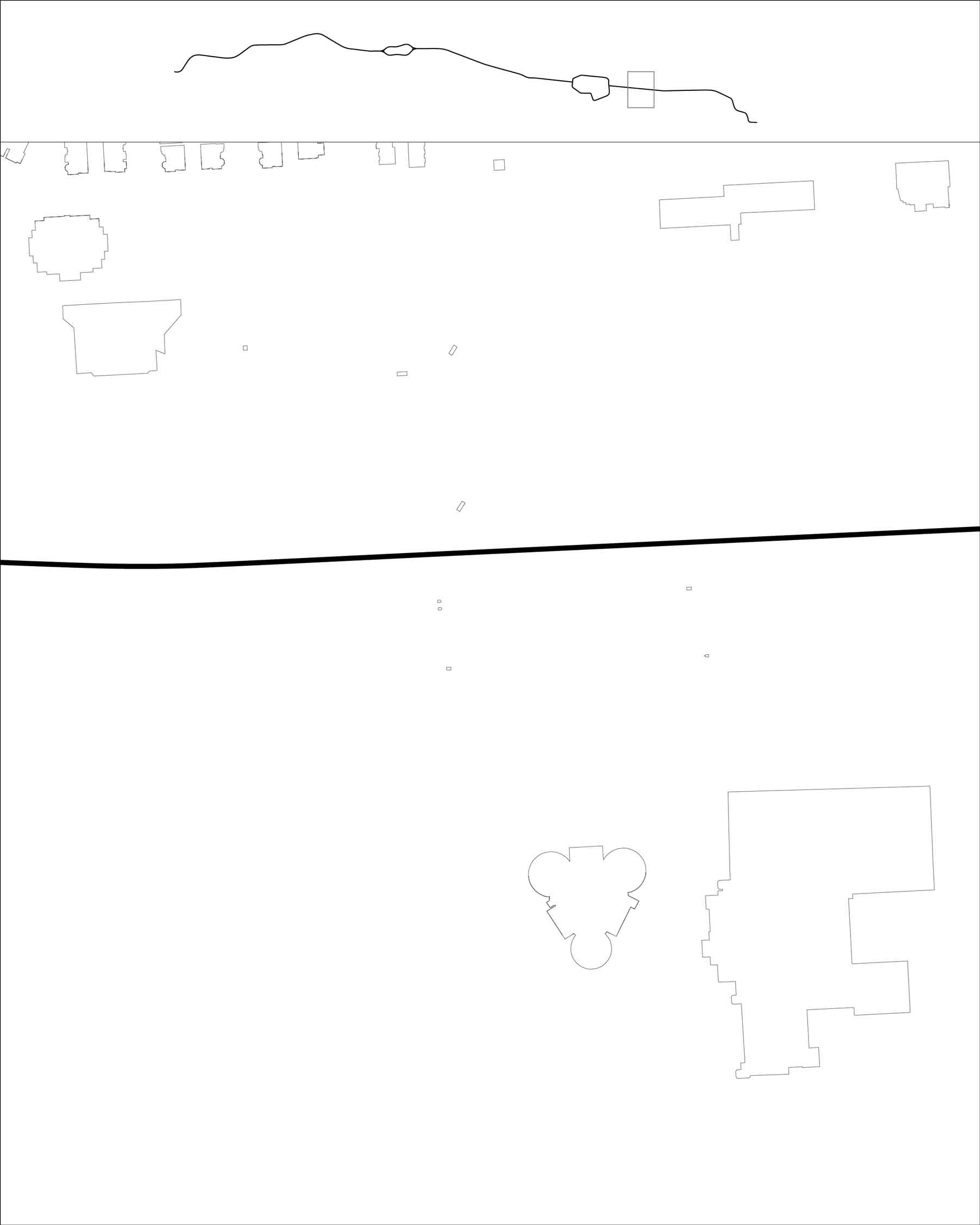

The only thing that holds many such enclaves together are the major roads that provide access to them, many of which, such as is the case in Canada and the U.S., have been built along the great land grids of the late 1700’s and early 1800’s:

The Hudson’s dominion grid in central Canada, Thomas Jefferson’s Public Land Survey System, and the Concession grid of Upper Canada. This last grid, which was the first at such a large scale to be realized, is the survey system that organized what is now the Greater Toronto Area. These roads which tile much of Canada and the United States were initially designed to promote land settlement in order to cement dominion over those lands by the authorities who commissioned them.

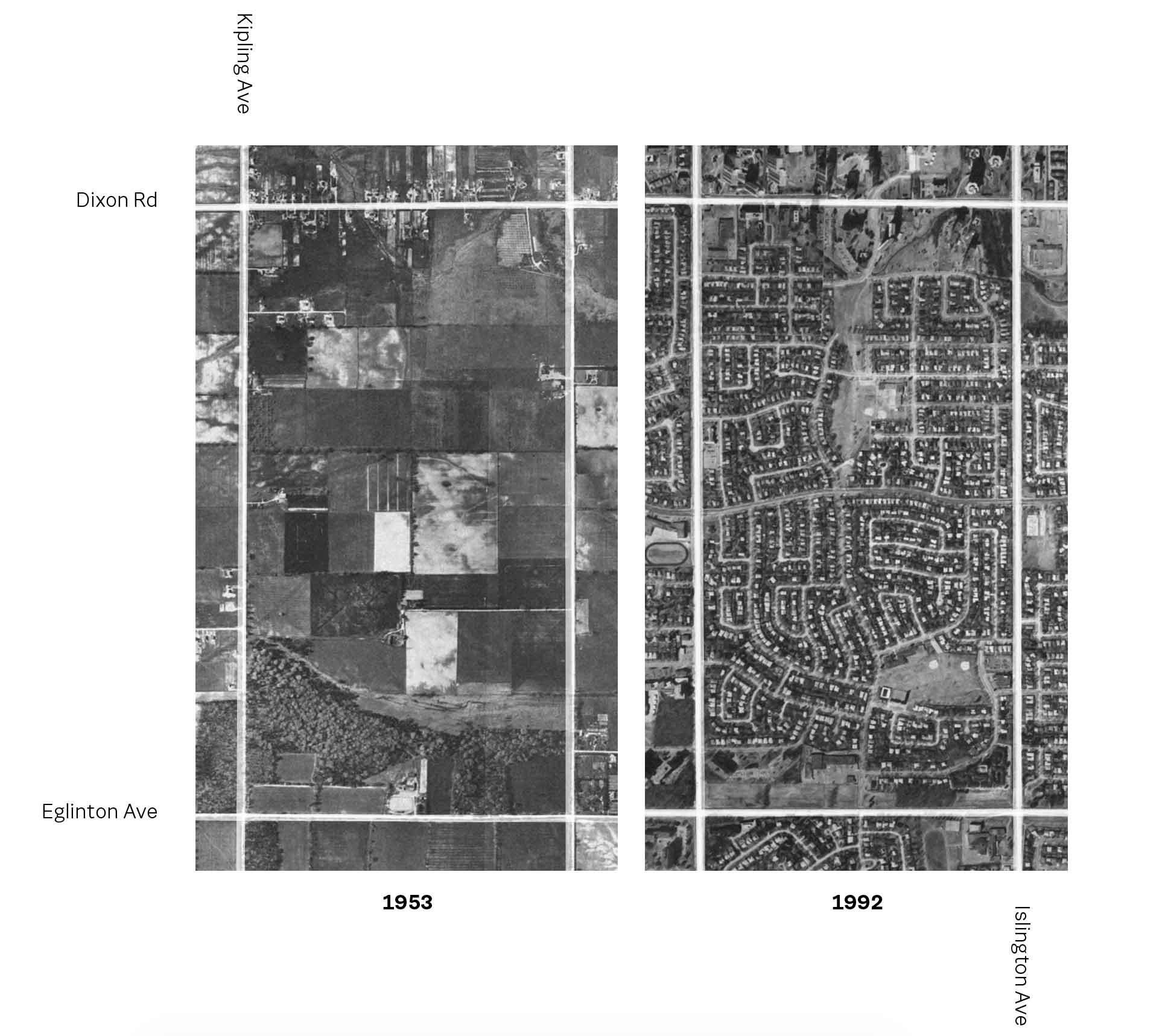

During the post war years, the grid provided a structure for a form of territorial development that was previously unprecedented in scale.

The Hudson’s dominion grid in central Canada, Thomas Jefferson’s Public Land Survey System, and the Concession grid of Upper Canada. This last grid, which was the first at such a large scale to be realized, is the survey system that organized what is now the Greater Toronto Area. These roads which tile much of Canada and the United States were initially designed to promote land settlement in order to cement dominion over those lands by the authorities who commissioned them.

The grid is a kind of public structure that enables freedom among its inhabitants to realize their own private dreams.

This system of private enclave building has informed a particular politics of collectivity within market driven urbanization in the United States. According to this ideal, the role of public institutions and their infrastructures is to be a kind of neutral framework for private ideals… as if such neutrality is ever possible.

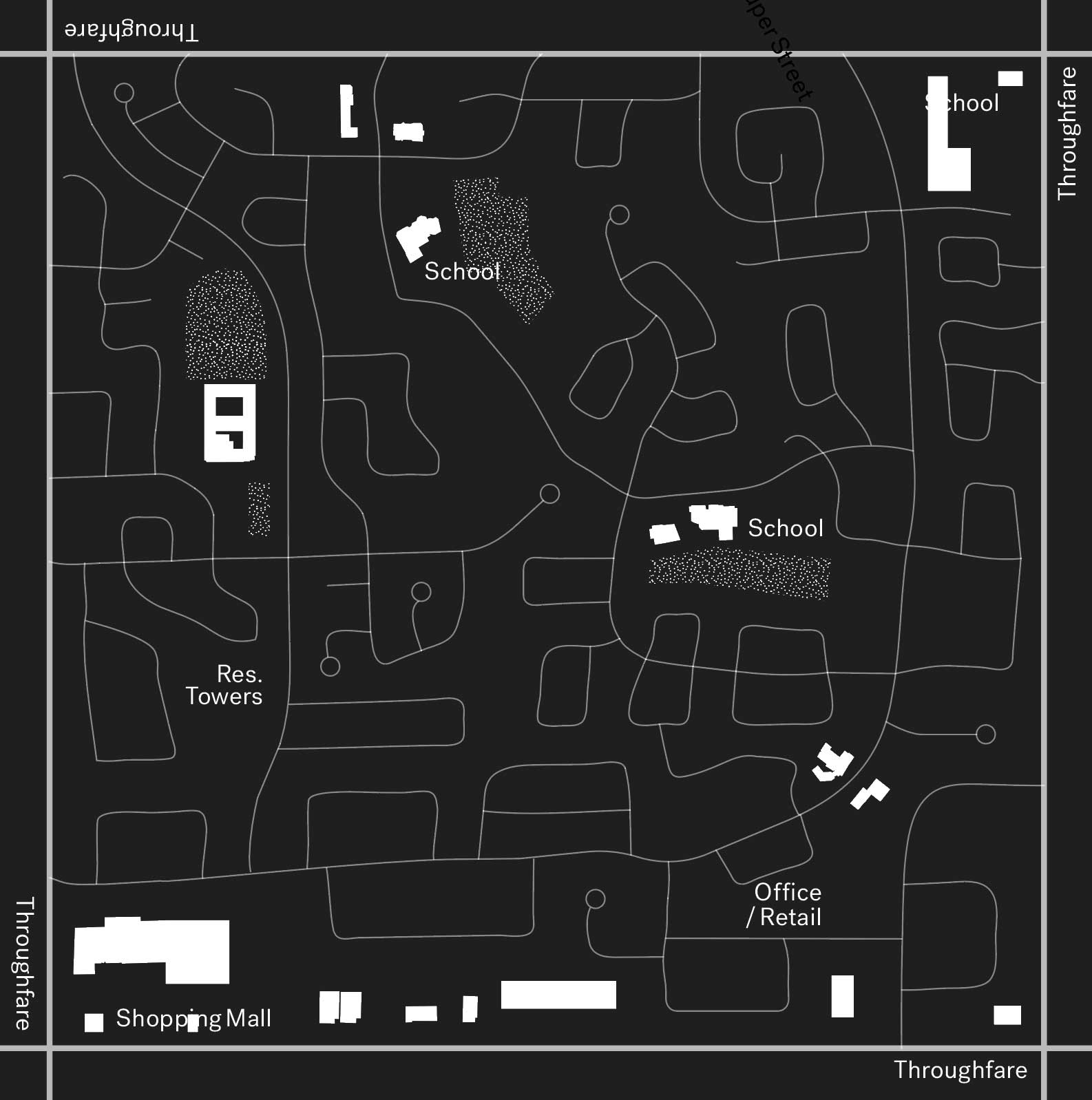

In Canada, and in Toronto particularly, mass suburbanization was different.

Like the United States, Toronto’s, postwar suburbs were structured by an underlying land survey system, on which arterial roads would be built and within which distinct enclave subdivisions would be produced. Beyond these traits, peripheral urbanization in Toronto is different. Here, neighborhood enclaves were not built one superblock at a time by uncoordinated, private individuals; but were rather structured by a process of multi-block planning. Central agencies gathered private landowners and together they would determine the location of public schools and parks, areas for apartments and commercial activity, and — most notably for our purposes here — the pattern and organization of public roads.

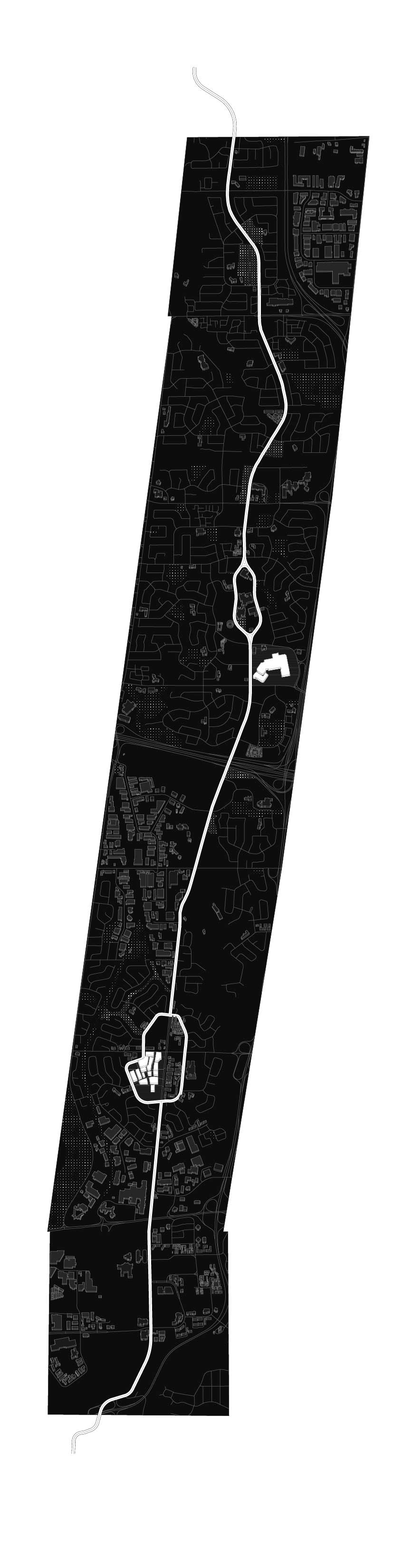

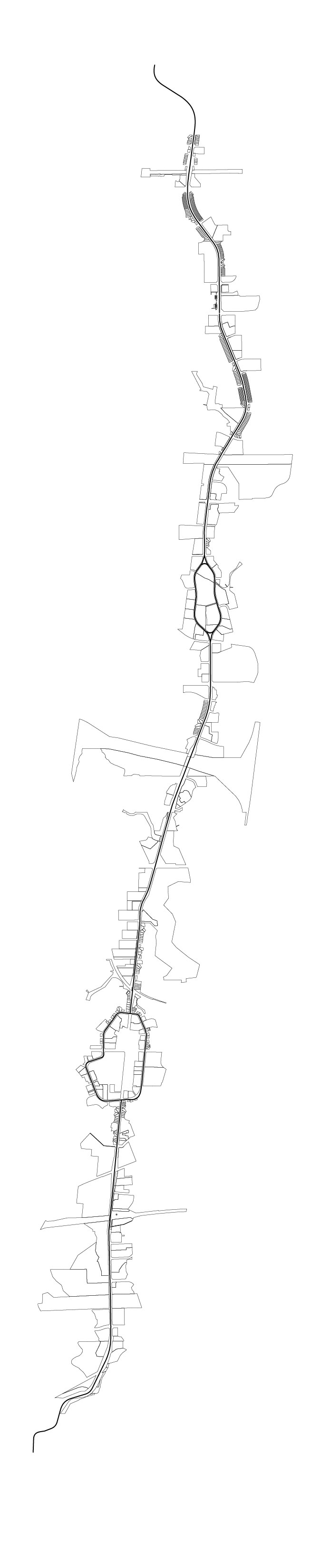

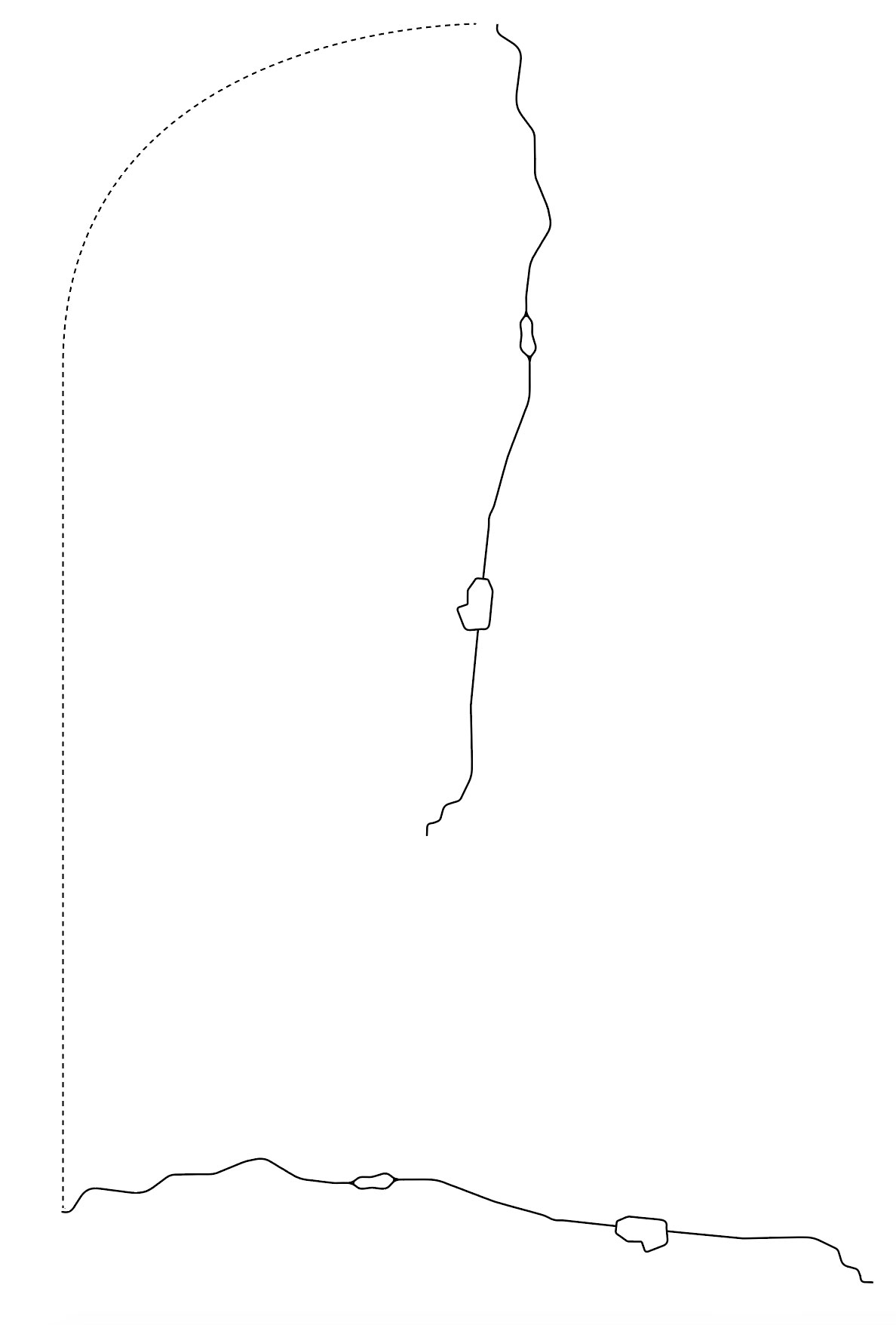

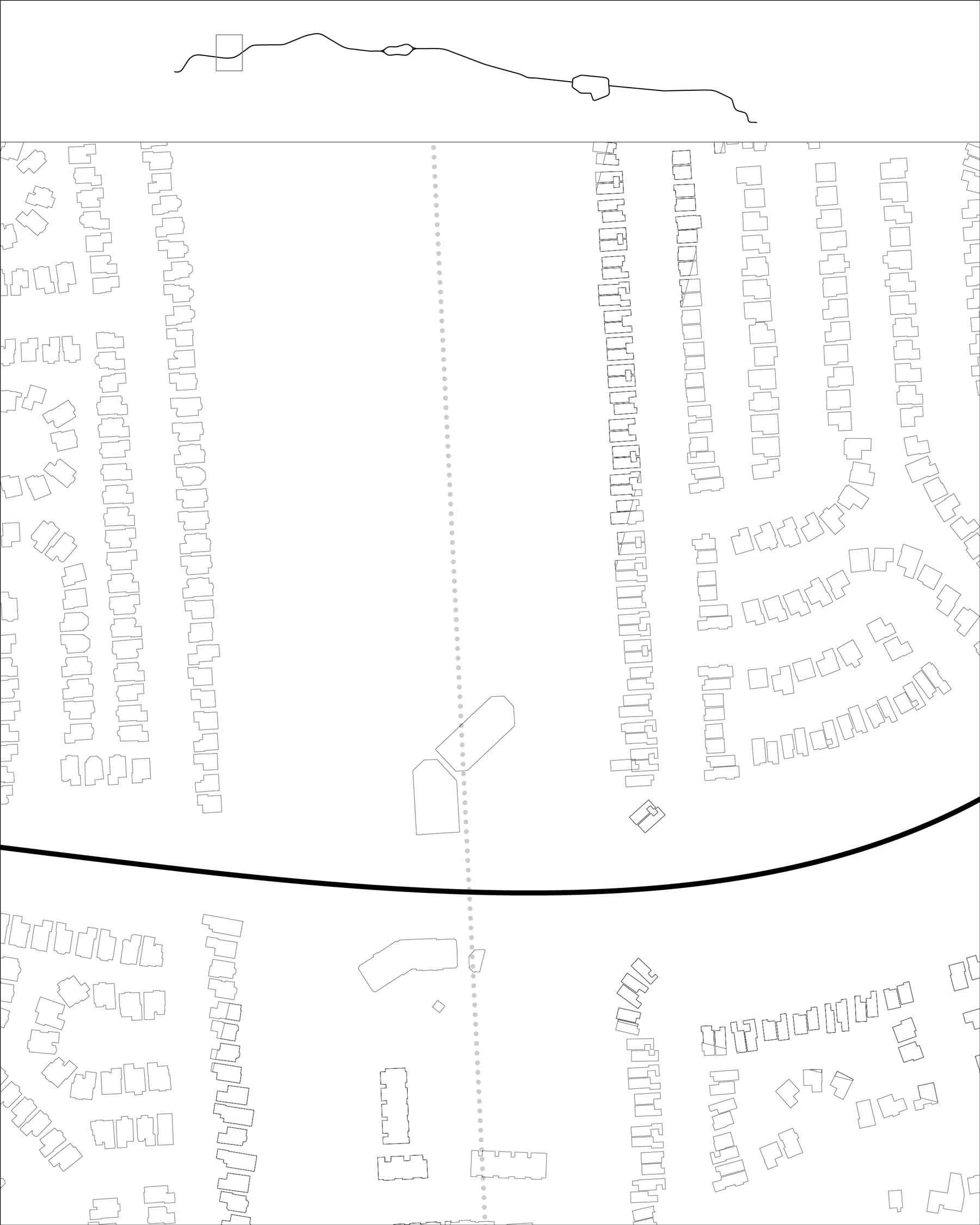

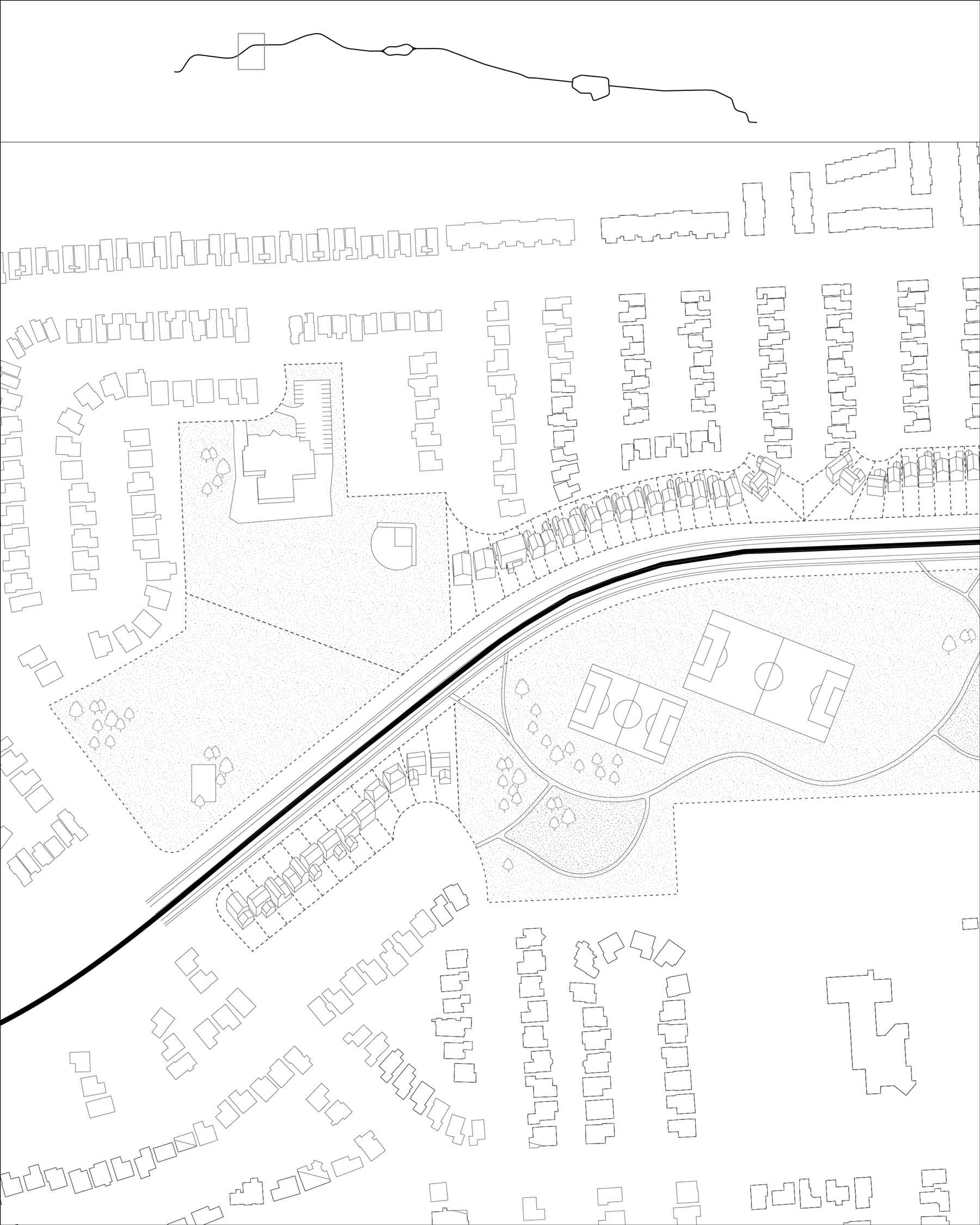

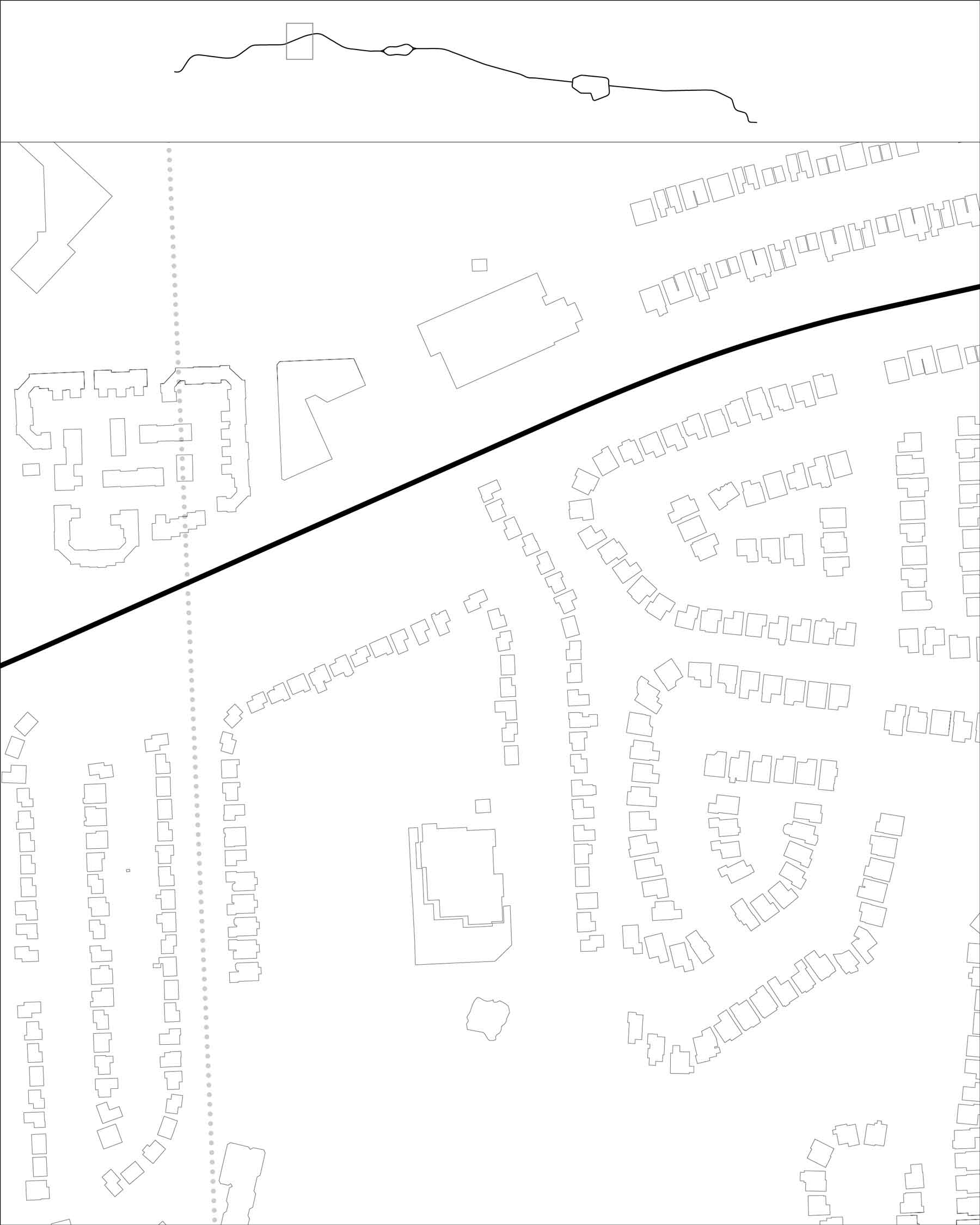

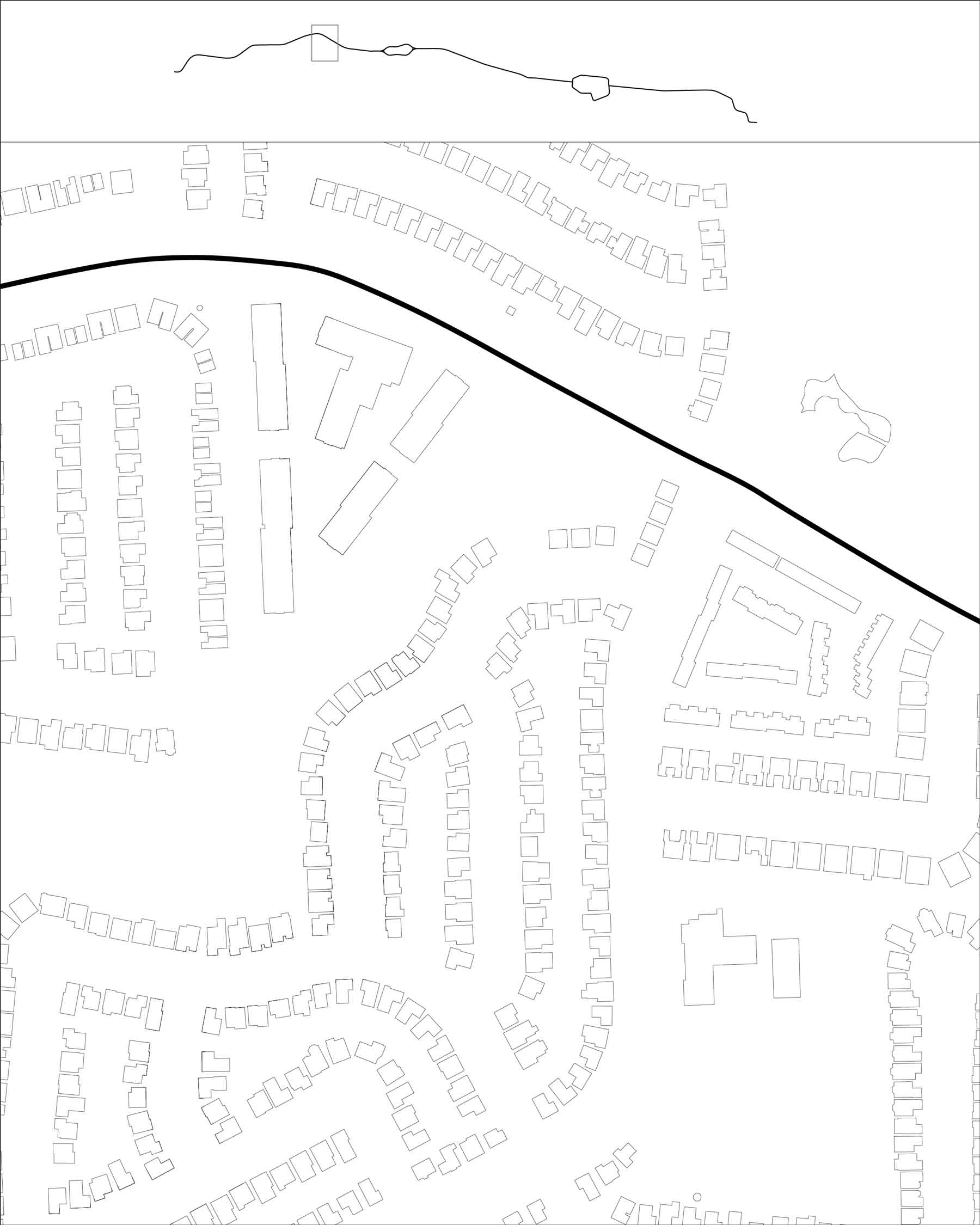

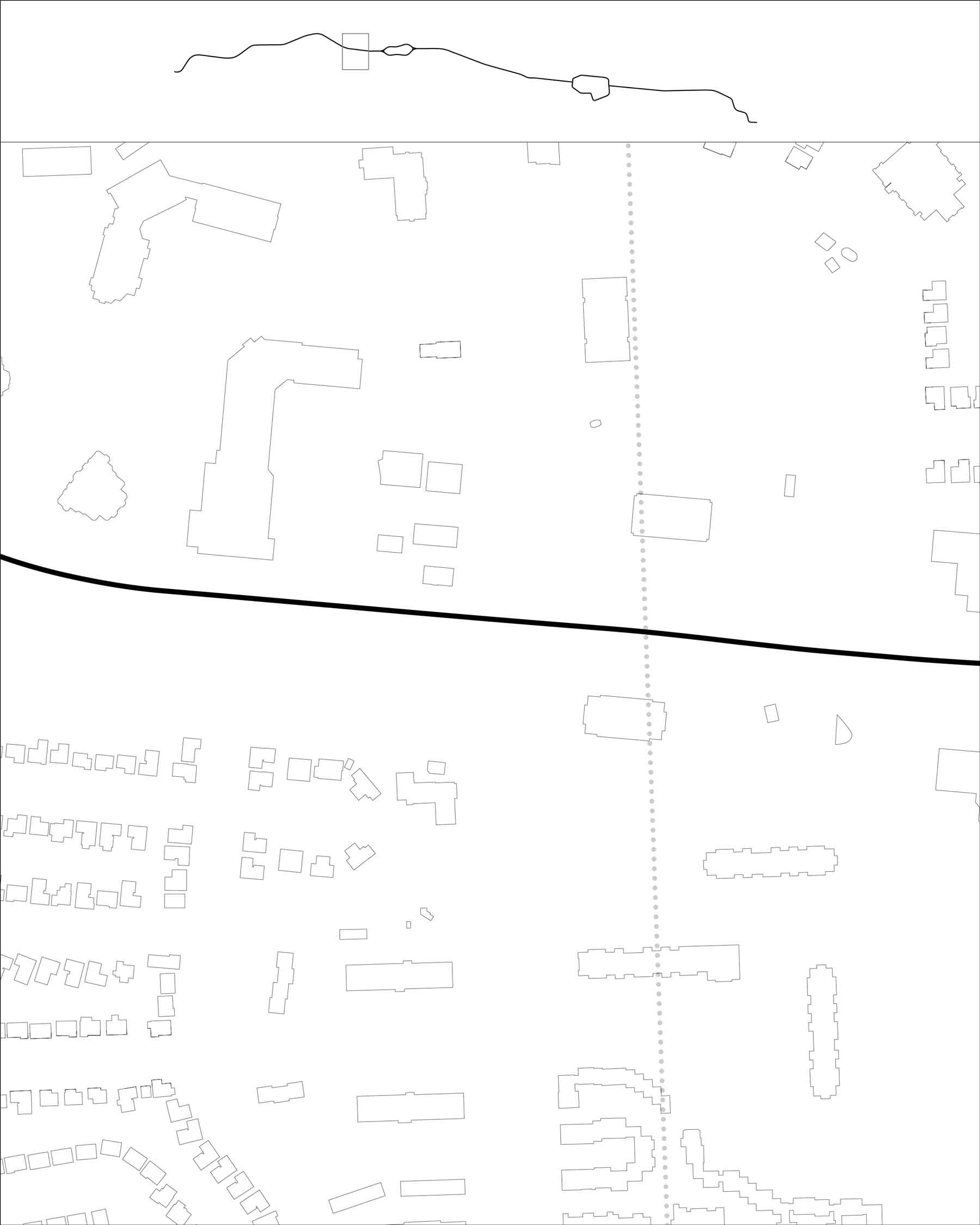

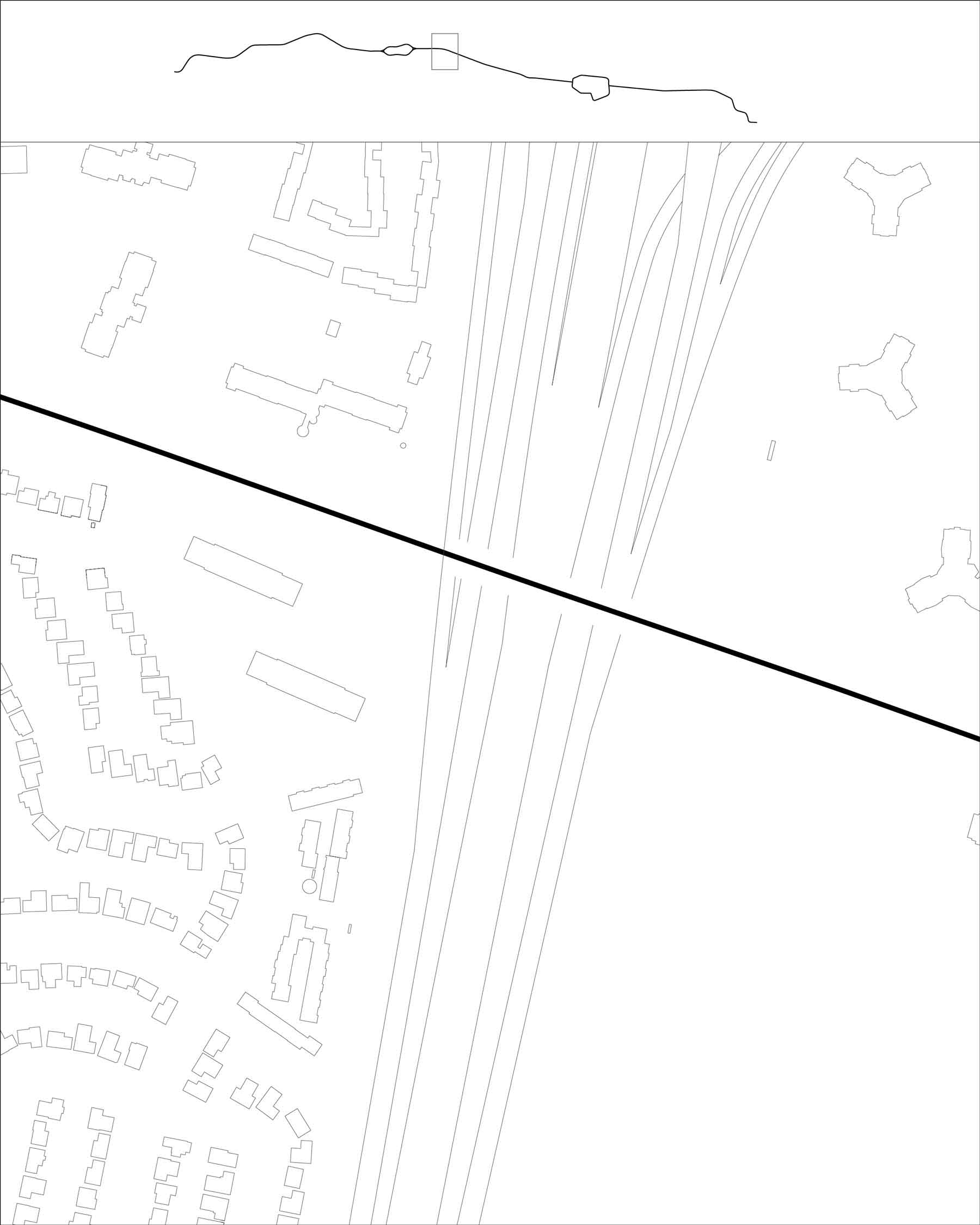

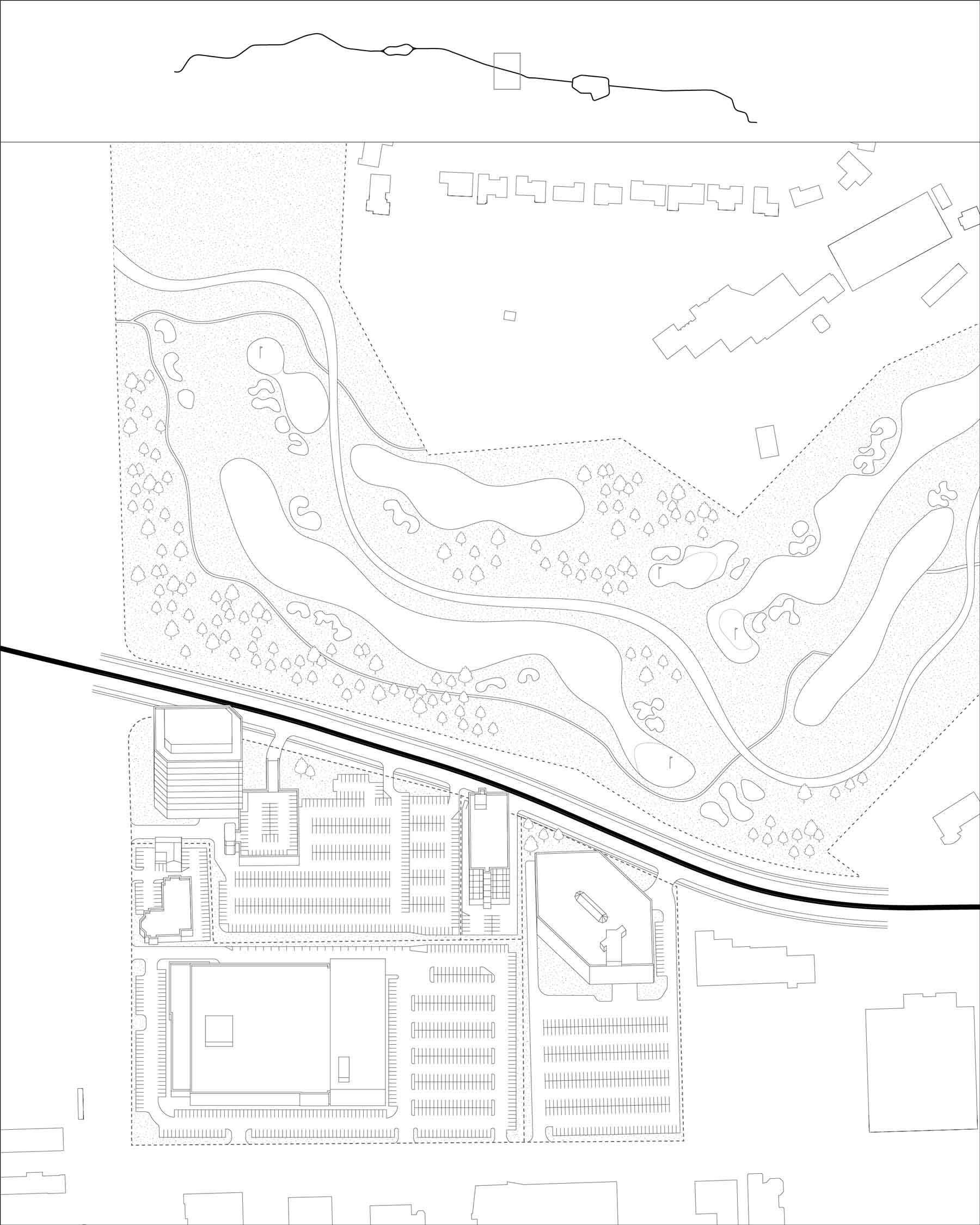

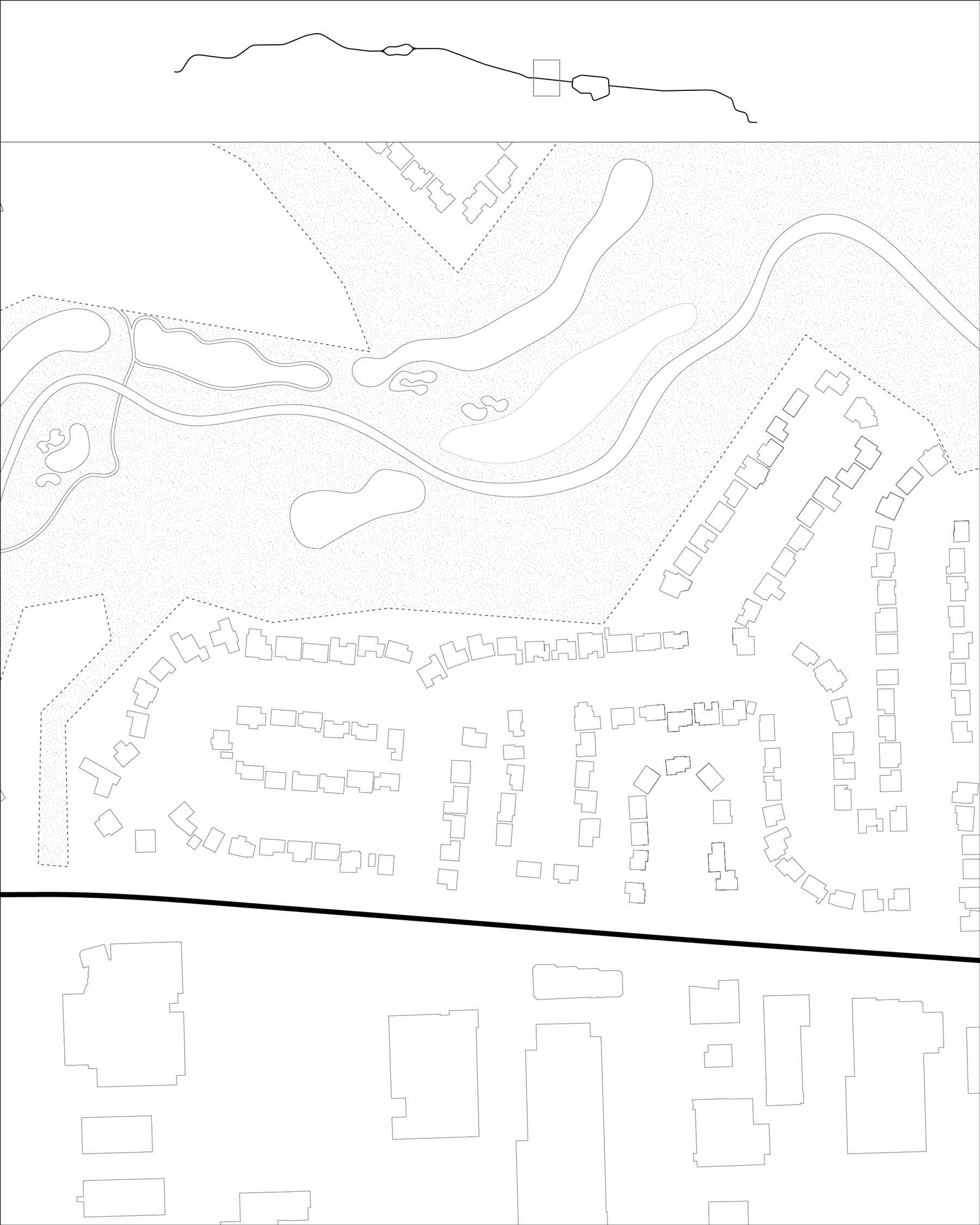

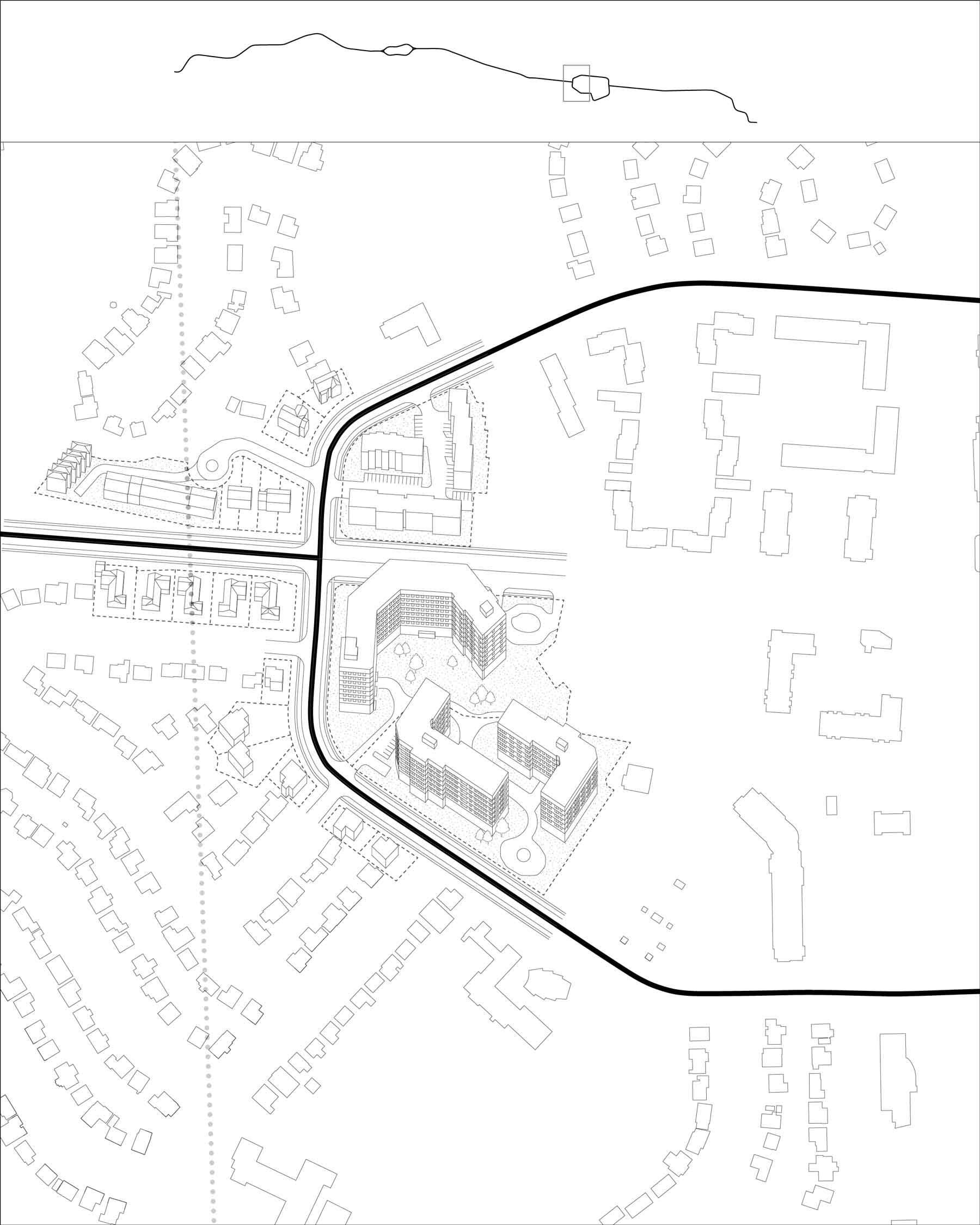

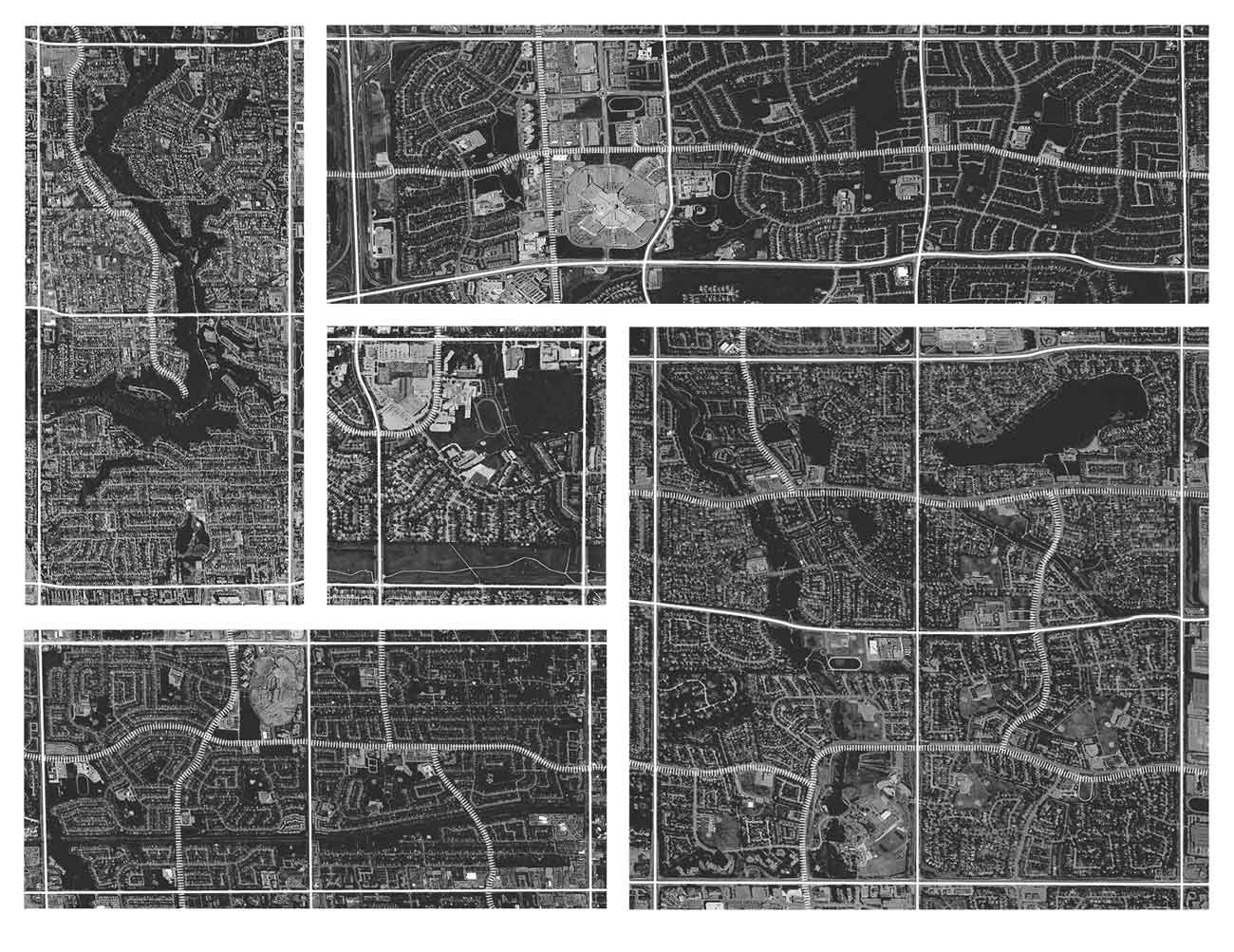

Within this process, individual residential neighborhoods were connected by a series of figural roads, what we’re calling Superstreets.

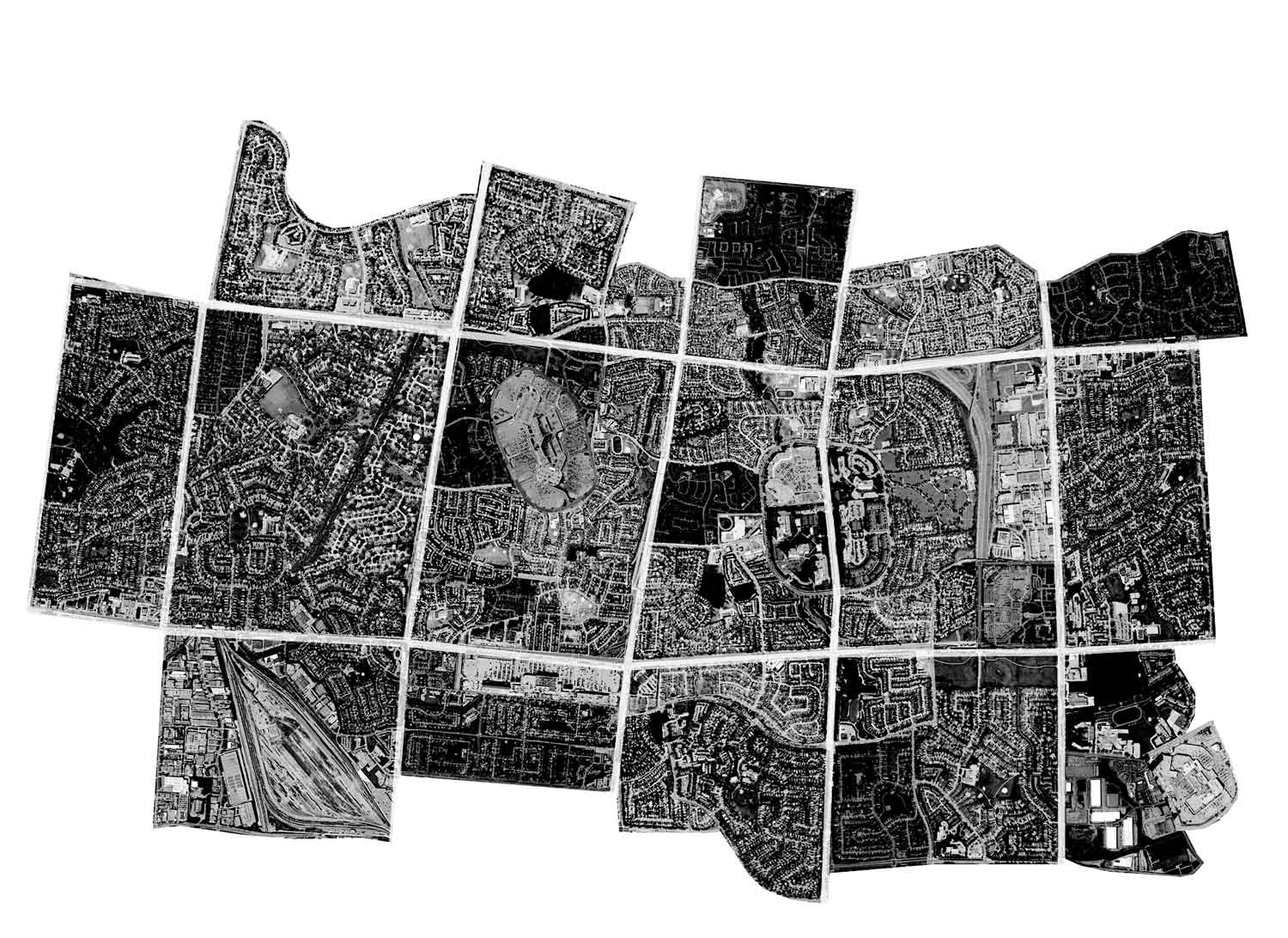

Their curving forms would cross the underlying grid lines providing legible passage between adjacent subdivisions. Our map drawing (see pages 14,15, 16) highlights the series of adjacent block developments in black, and shows the Superstreets crossing between them in white. They were clearly designed with a particular formal ambition. Against the rigid land grid, they read as free-form characters. By our estimation, they take on an animal-like shape, a quality by which we have affectionately named them.

Beyond their formal and graphic quality, we recognize the utility of Superstreets.

Not only do they connect adjacent neighborhood enclaves, they also provided access to higher density apartment towers, shopping malls, community buildings or other conditions. As such, these roads suggest a form of collectivity within the vast space of otherwise private-looking suburbia.

The collective form we see in these streets is of a very particular nature. Superstreets are not walkable — a metric commonly used by planners and designers to measure the public or common nature of a place — but are collective for the fact that they challenge some of the barriers of private land-ownership that otherwise inform the majority of similar development in the United States. For sure, Toronto’s suburbs are spread out and are often as unpleasant to experience as a pedestrian as they are in the U.S.

But as designers and planners go about the task of remaking or reforming the broader suburban landscape, it is instructive to see that the built form of these places often belies the unplanned, neo-liberal disorder that their physical appearance suggests.